Chinese Triads launder billions through Vancouver, buying luxury real estate, cars

British Columbia launches public inquiry after Triad activities drive up cost of homes

The laundering scheme is so infamous that investigators call it the “Vancouver model.”

The Triads, China’s organized crime syndicate, created a pipeline that laundered $4 billion in illegal drug profits last year through real estate and other investments in Vancouver, British Columbia. The conspiracy, news of which has scandalized the province’s largest city, starts in China, where precursor drugs used to manufacture the deadly opioid fentanyl are shipped to the Port of Vancouver and sold on the streets by drug dealers. The dealers drop the money off with Chinese gamblers who launder it by purchasing betting chips at high-roller tables in the city’s casinos and cashing them out. They then deposit the “washed” money into underground banks that wire the funds back to the Triads in China.

Thereafter, the funds are transferred to shell companies – protected by Canadian privacy laws – and used to buy luxury homes and expensive cars in Vancouver. In 2018, the Triads laundered $5.4 billion ($7.4 billion Canadian) in the city, according to provincial government figures. Of that, the criminals invested $4 billion in real estate alone, which has increased the cost of homes in Vancouver by five percent. The bubble in prices is so large that the city’s residents complain they no longer can afford to buy a home.

David Eby, British Columbia’s attorney general, uncovered a great number of cases of real estate bought thanks to laundered money, going back years. A person claiming to be a student purchased 15 condominiums in one building in Vancouver in 2001 for $2.1 million, and the units would sell today for $8.1 million. A woman dubbed a “homemaker” paid $3 million for 12 houses in the city’s downtown from 2004 to 2007, and those are now worth $11 million.

The revelations came from two reports based on government studies released in May by British Columbia to examine the extent of money laundering there. One of the studies, announced by former provincial attorney general Maureen Maloney, determined that the problem is nationwide – organized crime washed an estimated $34.8 billion within Canada in 2018. More of it came through Canada’s Ontario, Alberta and Prairie provinces than in British Columbia.

The source of the drug money that starts the Triads’ laundering process is Guangdong, China’s most populous and richest province (with more resident billionaires than anywhere in the country) located along the South China Sea. Near the financial center of Hong Kong and China’s casino capital of Macau, Guangdong is ripe for exchanging money overseas. It’s also the location of chemical factories that manufacture the synthetic opioid fentanyl and chemical precursors used to make the dangerous and addictive drug.

The narcotics are smuggled from Guangdong to Vancouver by the Triads, who have had a foothold in Vancouver since the 1990s. One method of hiding drug money is to transmit it to an offshore bank. A Triad member obtains a “legitimate” loan from the bank to buy real estate. A strawman or stand-in buyer then purchases a luxury home or condo at a much higher reported price than the one paid by the Triad member, who makes a bigger profit. In the process, real estate values in Vancouver are inflated.

Meanwhile, seizures of Chinese-made fentanyl by Canadian authorities increased by almost three times in 2016-2017 compared with 2014. In 2017, of the more than 1,400 people who died of drug overdoses in British Columbia, about eighty percent had used fentanyl by itself or mixed with other drugs.

“Whether you’re talking about fentanyl or whether you’re talking about real estate, it’s a crisis,” Eby said during an interview on CKNW radio in British Columbia.

So-called casino junket operators also facilitate the laundering of drug money in Vancouver. Junket operators lend money to high-rolling gamblers to purchase casino chips. The gamblers, in a classic money-laundering ruse, “wash” these loans by cashing in the chips and using the money to acquire expensive housing.

According to Eby, casinos in British Columbia permit hoodlums to bring in hockey bags full of hundreds of thousands of Canadian dollars from the sale of synthetic opioids and buy casino chips. Nothing happens to them.

Further, sellers of high-end automobiles in Vancouver have no incentive to report suspiciously large cash sales. Launderers will have strawmen buy the luxury cars and ship them off to China.

The players in the laundering plot in Vancouver are not just from China, according to Peter German, a former investigator for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who wrote one of the government reports on money laundering. “It is alarming to know that Greater Vancouver has also acted as a laundromat for foreign organized crime, including a Mexican cartel, Iranian and mainland Chinese organized crime, all seeking a safe and effective locale in which to wash their proceeds of crime,” German wrote in his report, as quoted by The Canadian Press.

German cited a number of reasons why the launderers are able to bypass regulators: the use of private mortgages by criminals to hide the source of the funds, strawmen buying properties, hard-to-track cash purchases, poor reporting by real estate salespeople about suspicious activities, and British Columbia’s owner-friendly land title rules that help hide the names of buyers.

He also criticized the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Center of Canada, or FINTRAC, the national agency tasked with investigating money laundering, for not adequately examining laundering in British Columbia and failing to exchange information with local police agencies.

On May 15, John Horgan, British Columbia’s premier, announced the start of an independent public inquiry into money laundering in the province. Horgan appointed B.C. Supreme Court Justice Austin Cullen to chair the investigation and gave Cullen the ability to order witnesses to testify and compel the production of documents. “That criminal activity has had a material impact on regular people, whether it was a rise in opioid deaths,” Horgan said, “or the extraordinary increase in housing costs.”

This story reveals more than just the failure of Canadian controls against money laundering. It highlights the current global problem of money laundering, in North America, Europe and the Middle East. Based on recent accounts, the criminals are winning.

Aside from the Vancouver scam, Russian-linked businessmen reportedly laundered $230 billion through the Denmark-based Danske bank in Estonia (mentioned in this column in March) in eastern Europe. Of that, $3 billion originated from the oil-rich nation and former Soviet republic of Azerbaijan, laundered from Danske’s Estonia office to shell companies in London.

On May 19, the CBS show 60 Minutes carried an interview with Howard Wilkinson, the whistleblower on his former employer, Danske. Wilkinson, a British citizen who worked at the Estonia branch, spoke about an astonishing $230 billion laundered through the branch by Russian interests. Probes into that huge operation are underway in the United States, the U.K., France, and Estonia. The laundering scheme included converting Russian rubles to U.S. currency, transferring millions a day to a shell company in London, and using more than sixty other shell companies and off-shore havens for hiding money, such as the Seychelles and the Marshall Islands.

Azerbaijan’s part of the Danske bank secret money transfers is known as “the Azerbaijan Laundromat.” From 2012 to 2014, $3 billion from the nation’s capital city Baku made its way to Danske in Estonia and then to four shell companies. The companies were entered on the U.K.’s official registry of businesses, Companies House, based in London, but without the names of the owners.

In 2017, Margaret Hodge, Britain’s former public accounts committee chair, charged that some of the Azerbaijan money was used “to curry influence and bribe European politicians” and to “line the pockets” of Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Alivev, his wife, children and their “cronies.”

On May 30, a committee organized by the European Union’s Council of Europe held its first meeting in Baku, Azerbaijan. With its stated goal “Strengthening Anti-Money Laundering and Asset Recovery in Azerbaijan,” the committee was set to examine, EU officials said, “institutional reforms aimed at enhancing capacities of Azerbaijani authorities to prevent and combat money laundering and terrorism financing, and recover proceeds from crime in line with European and international standards.”

U.S. TREASURY: TWO MEXICAN POLS CORRUPTED BY CARTELS

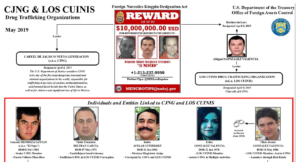

U.S. Treasury officials have designated a judge and a one-time state governor in Mexico as corrupt individuals along with a number of civilians with alleged ties to the Cartel de Jalisco New Generation (CJNG) and Los Cuinis drug trafficking organizations.

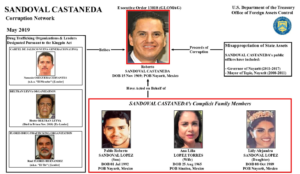

The Office of Foreign Assets Control, part of the U.S. Treasury Department, alleges that Mexican magistrate Judge Isidro Avelar Gutierrez and former Nayarit Governor Roberto Sandoval Castaneda were paid to engage in crooked acts to benefit the CJNG and Los Cuinis.

As a result, the United States has imposed strict economic sanctions on both men, some of their relatives, acquaintances and businesses. All property or businesses owned, directly or indirectly, fifty percent or more by Gutierrez and Castaneda or the others designated as their cohorts, within the United States or possessed or controlled by someone in the U.S., can no longer engage legally in financial transactions.

The U.S. Justice Department considers the CJNG one of the five most dangerous transnational organized crime groups in the world. The cartel traffics tons of cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin laced with fentanyl into the United States and commits violence and murders in Mexico. The CJNG is headed by two brothers-in-law, Nemesio Oseguera “El Mencho” Cervantes, who is a fugitive, and Abigael Gonzales Valencia, now in jail in Mexico and awaiting extradition to the U.S.

The Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, or Kingpin Act, serves as the legal basis for the designation and sanctions against Gutierrez. The Kingpin Act enables the Treasury to enact penalties on businesses linked to organized crime, including those based in Mexico. In his position as judge, Gutierrez received bribes from the CJNG and Los Cuinis in exchange for tipping the scales in rulings in favor of their senior members, U.S. officials say.

The Office of Foreign Assets Control has in years past ordered sanctions against many Mexican businesses tied to the CJNG and Los Cuinis, from shopping centers and real estate firms to restaurants, a music promotion business and a luxury hotel.

The Treasury Department also sanctioned two of Gutierrez’s siblings, Ekira Gonzales Valencia and Ulises Jovani Gonzales Valencia, for their assistance in bribing government officials and laundering money for the two cartels. Two others sanctioned were Victor Francisco Beltran Garcia, a lawyer in Guadalajara who allegedly facilitated corrupt acts with the cartels, and Ulises Jovani Gonzales Valencia’s wife, Ana Paulina Barajas Sahd, who aided her husband.

Castaneda, who served as Nayarit’s governor from 2011 to 2017 and was mayor of the state’s capital city of Tepic from 2008 to 2011, is alleged to have misspent state funds and accepted bribes from the CJNG and another Mexican drug cartel, the Beltran Leyva Organization.

Treasury ordered sanctions against Castaneda using both the Kingpin Act and the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, which punishes those who commit serious abuses of human rights and corrupt acts. The agency placed sanctions on members of Castaneda’s family – his wife, adult daughter and son – who hold some of his assets in their names. Those assets, also sanctioned, include a butcher shop, clothing store, real estate firm and land holding business.

Others, including a top CJNG member, Gonzalo Mendoza “El Sapo” Gaytan, and Gaytan’s subordinates, allegedly involved in many murders and kidnappings, received the designation under the Kingpin Act. Gaytan controls drug trafficking in the resort area of Puerto Vallarta. The U.S. also designated Gaytan’s wife, Liliana Roses Camba, who allegedly manages businesses that launder his proceeds from drug trafficking.

The department ordered injunctions on six businesses in the Jalisco area in Guadalajara cited as fronts for Gaytan, including two architectural-real estate firms, an organic products company and a woman’s clothing shop.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org